Prague has filled my imagination for decades. In an earlier post I mentioned growing up with kids of Bohemian, Moravian, and Czech background. My best buddy in HS, Johnny Krupka, traces his roots to a town north of Prague and his great-grandfather came from Prague in the early part of the 20th century as a sculptor and set up a studio in NYC. Johnny traces his own artistic interest back to him. Some of you know of my love of Willa Cather’s novel, My Antonia, that tells the story of a remarkable immigrant family from Bohemia homesteading on the Nebraska plains. But it was likely that even more than Amadeus (’84), it was the moving film Yentl (’83), starring Barbara Streisand, Amy Irving, and Mandy Potinkin, that fueled my imagination to see the city in person. It truly is the most “old-world” city in the Old World. Trust me: it did not disappoint!

Yesterday morning we said good-bye to our ship, that wonderful floating hotel, boarded a bus, and drove the 3.5 hours to Prague. Have I mentioned that as we came over the mountains there was new-fallen snow on the ground? Thankfully by the time we arrived the sky had cleared, and it warmed up enough to be comfortable. After checking in Amy and I walked to a traditional Czech restaurant for lunch. Alec Koukol forgot to mention that they try to kill you with potatoes! I think they served Amy and me enough for a family of 6.

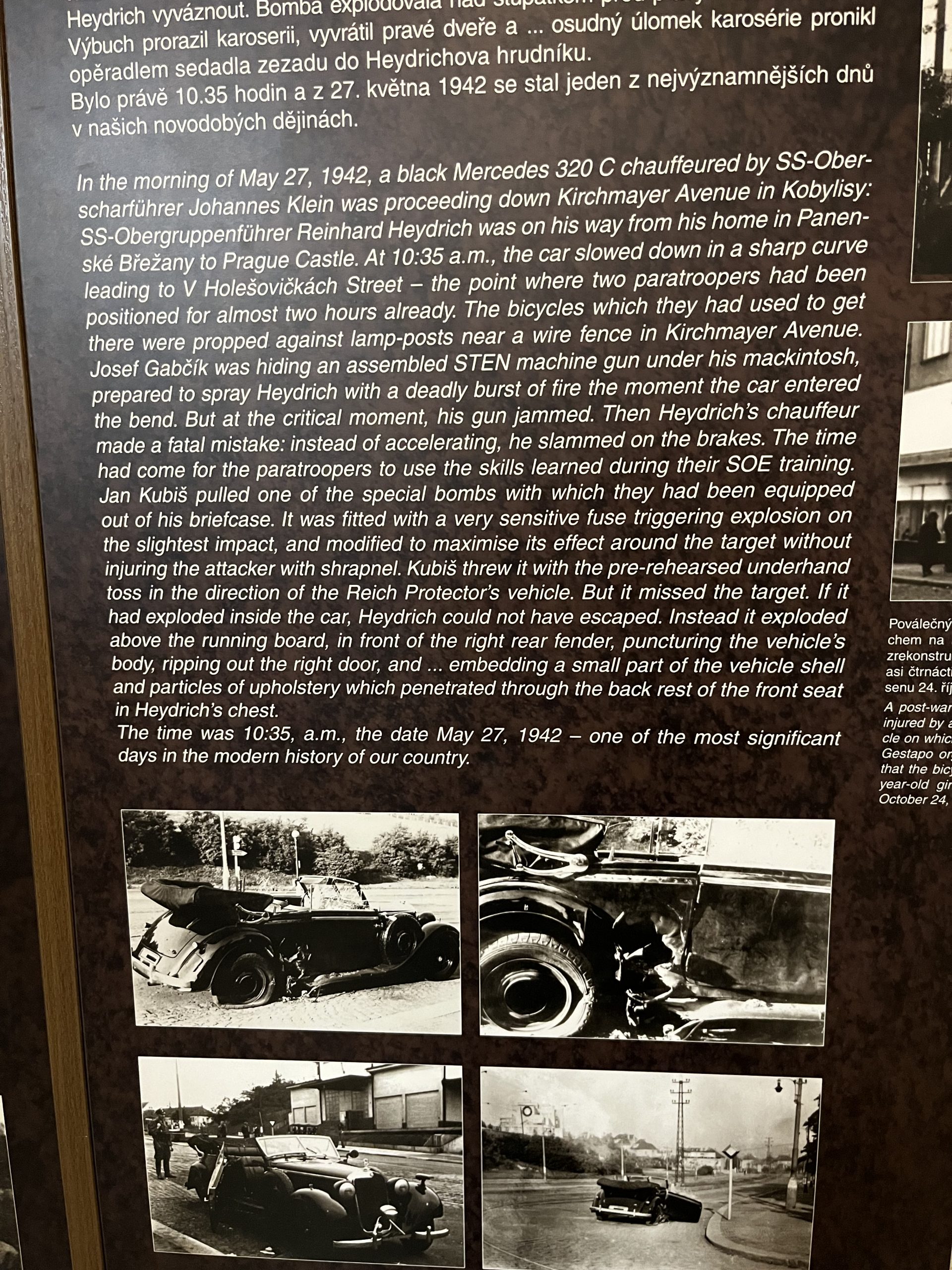

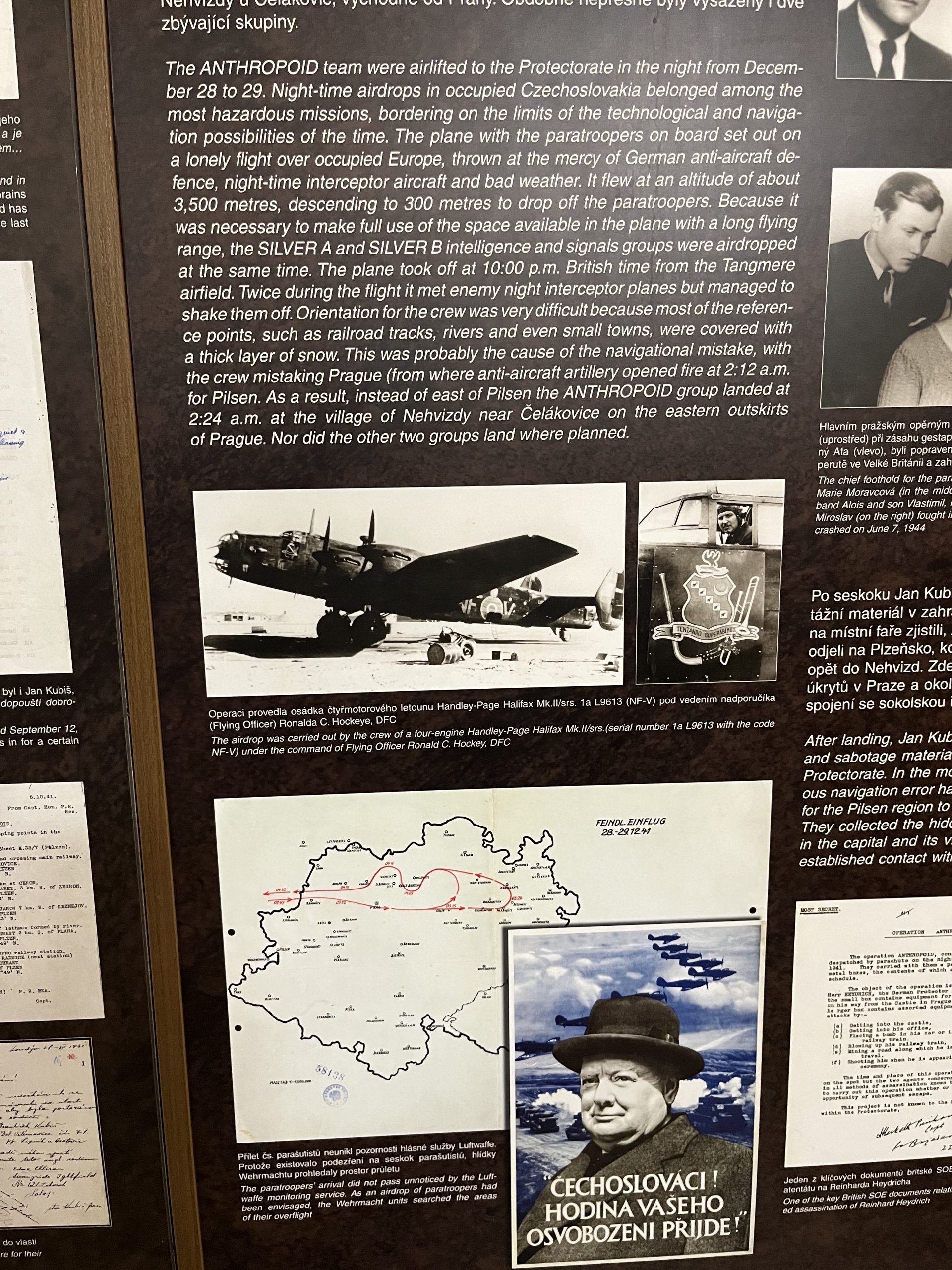

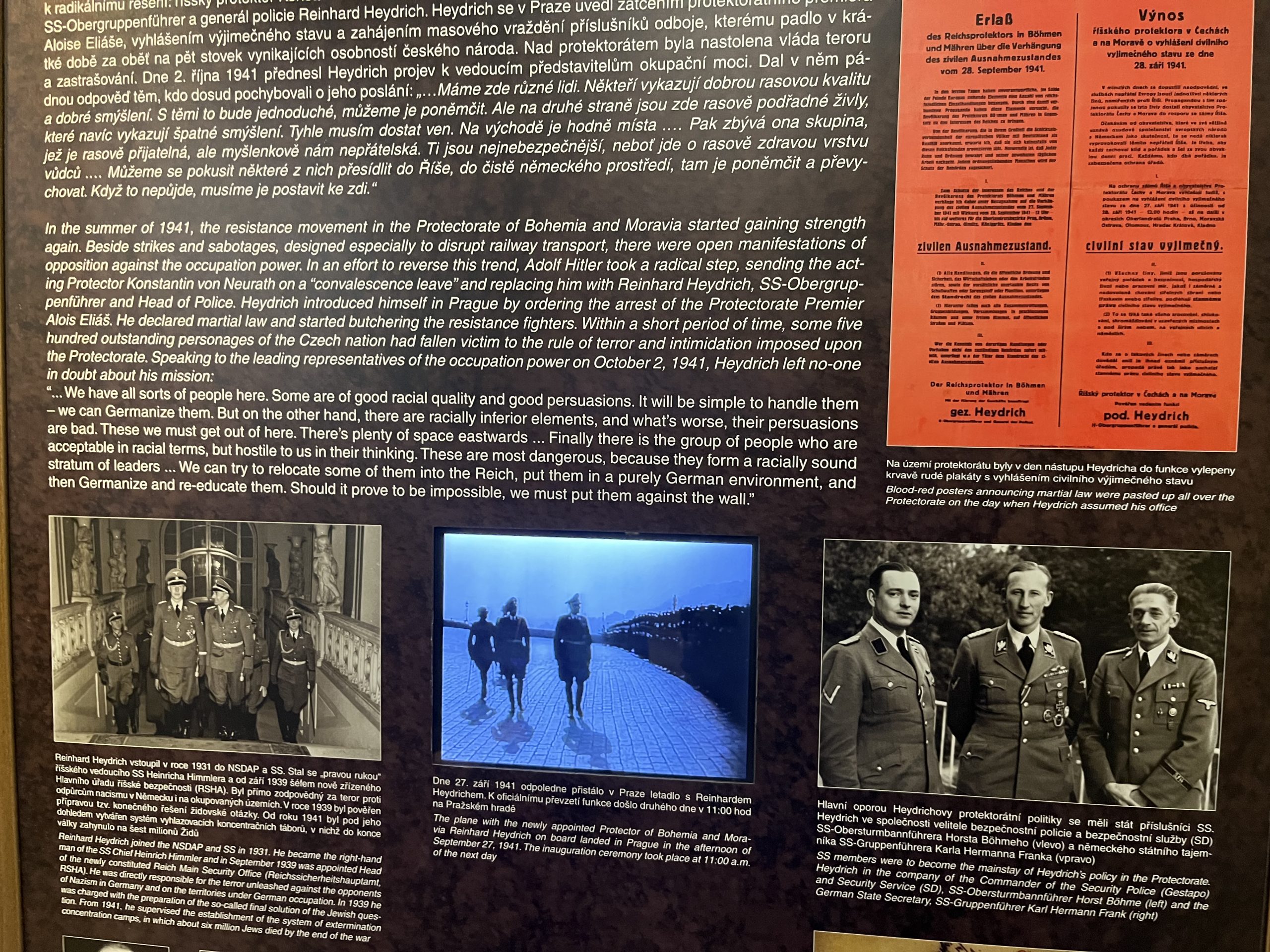

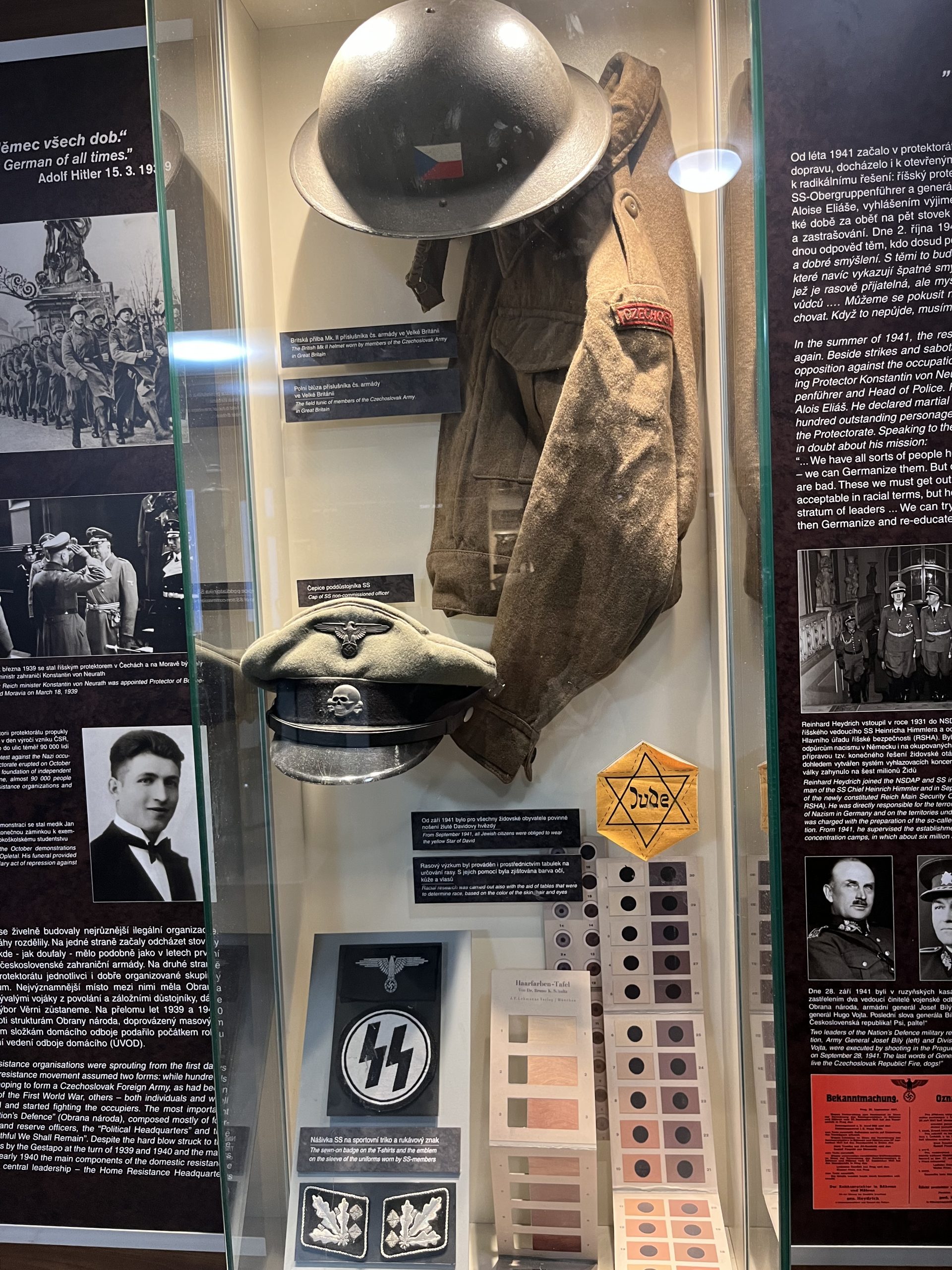

Fortified we headed out with a private guide to tour the city and see the sights connected with one of the most famous events in 20th century Czech history: the successful assassination of the third highest ranking Nazi officer, Reinhard Heydrich, one of the primary designers of “final solution.” Code-named “Operation Anthropoid” select Czechoslovakian soldiers trained in Scotland by the British SOE, and were secretly parachuted into their homeland and smuggled into Prague to carry out the operation. Ultimately, they were trapped in a crypt of an Orthodox Church, which was right across the street from where our guide went to high school (a large, impressive, yellow building). We were grateful to hear from his perspective, especially how Czech history was taught when he was a boy during the Cold War. Two examples: first was they were taught that the soldiers were wrong for committing the assassination, because the Soviet-backed government were concerned that seeing the soldiers as heroes would fuel nationalistic pride and cause young people to want to throw off Soviet control. The other was how they taught Jan Hus – the great proto-Reformer who was burned at the stake in 1415. He was a Czech theologian and philosopher who became a Church Reformer and provided the insights to the Hussitism, a key predecessor to Luther and the other Reformers who came a century later. Michael said what was focused was Hus’ critique of the Church’s wealth, which would fit with a communist perspective. I have studied Hus for years as a champion of the kinds of Reform that would come later, especially translating the Bible into the language of the people. Churches such as The Moravians (who founded my hometown in 1740), the Lollards, the Waldensians, the Amish, and the Mennonites, all trace some of their spiritual DNA back to Hus.

What I found so disturbingly paradoxical is while Prague proudly calls itself “The City of Spires” (and it is!) essentially 80% of the residents of the Czech Republic do not declare having any religion or faith in surveys, and the proportion of convinced atheists (30%) is the third highest in the world behind those of China and Japan. All these beautiful churches that are crowded with tourists are basically aesthetically pleasing cultural curiosities rather than vibrant worshipping communities. It made me a sad to see what has happened to Hus’ bold witness.