Alfred Edwin Drake – Dad |

I was ordained and then installed as an Associate Pastor at First Presbyterian Church in Morganton, NC, on Sunday, July 19, 1992. The date happened to land on my mother’s birthday. My dad had the sermon for the service. He entitled it “Navigating by a Few Unseen Daytime Stars,” which was based on scripture and a poem entitled The Helmsman, written by W.S. Merwin. The poem is about two navigators who are on the same ship. One navigates the ship at night by plotting the course by stars, while the other navigates “by a few daytime stars, which he never sees except as black calculations on white paper.” They are two people on the same voyage, who each “never sees the other, the earth itself is always between them.”

There is many a son who seeks to arrive on the other side and discover his father. I count myself as one of them. What on earth makes a father tick? My mother was easier for me to read, perhaps because she wrote newspaper columns and short stories and laughed at irony.

My father was all Greek to me. It was a language of love for my father – the Koine Greek of the New Testament. I think that he was on a path to becoming a professor of Greek studies, but some collision of ego and academic politics left him with no grace to continue. My dad returned to the church and, oddly enough, to fund-raising for the Presbyterian Church and later for small church-related colleges. My sister and brother paid the price of constant moves. I had a few, but my moves were better timed.

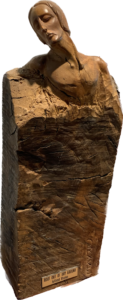

As an outlet from fund-raising, my dad found another love in shaping scripture into wood. His sculptures are based on scriptures. As I write this, I am in the company of his sculptures with names like “Benediction” and “Root Out of Dry Ground.” I see the sculptures, but I also hear the rhythms of his mallet and chisel. The artist is eternal.

When Dad returned to ministry, he returned fully to his love of Greek. He began to see patterns in the Greek declensions used in some of the pseudo-Pauline letters. He had a paper published in New Testament Studies on “Riddles in Colossians.” My paper is on the “Riddle of a Father,” a brilliantly mysterious man.

A therapist might say that my inclination to ministry was my attempt to communicate with my father, but I don’t think so. I entered ministry because of the people in the church. In my high school days, Lizzy Cullison, a ninety-eight-year-old woman, would follow me with lawn darts, stabbing them into the ground to indicate a place that I had missed in mowing. Mrs. Lamb knew the way to my heart was through my stomach and would invite me up onto her porch for sugar cookies and stories about her husband. Clarence Opell was a retired baker who would make huge sheet cakes for a birthday, a graduation or any month containing a third Tuesday. Earl Miller, who fought in the cavalry during World War I, served our Sunday School class fermented apple juice – Christian Education with a hangover!

All of these people had the most interesting lives and cared for me because I listened. What I had a hard time hearing was my father. Looking back, I can see how he sent me weekly letters that detailed the nuances of the Greek in the lectionary passages. My mother told me that he often cried when I preached. (I took that to be a good thing!) It was fascinating to see his joy and care in each grandchild born. These are some of the calculations he left and the direction we share.

One time we all traveled to the ocean. There on the beach, I suffered a severe back spasm. I could see, over the horizon of a beach towel fold, Beth and the kids playing a hundred yards away, but I couldn’t breathe. From on high, my father saw me, came down and picked me up. From there we traveled to the nearest “doc in a box” for a muscle relaxer that was injected directly into my back. The instant relief caused a vasovagal reaction and a memory of my father’s care.

Six months later, I was listening to my father lie to a heart surgeon. “Have you had any chest pains?” “No.” “Dad!” Again, from the doctor, “Have you had any shortness of breath?” “No.” “Dad!” Three days later I was helping my father dry off, following his first shower after having quadruple bypass surgery. These are the calculations on our voyage together.

Twenty years later, I read my father his underlined scriptures. Dad had waited for my brother to arrive from Seattle. After Dad died, I woke up the next day and wondered how to preach my father’s funeral. Some spirit led me to a dark corner of the basement, where I blindly stuck my hand into a file, pulled out a few pages and moved under a dim lightbulb. “Perfect!” At that moment I thought of the poem that my father read at my ordination. I wondered, “What was that about?” I then moved toward the door and spotted a briefcase on a shelf. After flipping the latches, I opened the briefcase to find the poem taped to the inside lid:

The Helmsmen

The navigator of the day

plots his way by a few

daytime stars

which he never sees

except as black calculations

on white paper

worked out to the present

and even beyond

on a single plane

while on the same breathing voyage

the other navigator steers only

by what he sees

and he names for the visions of day

what he makes out in the dark void

over his head

he names for what he has never seen

what he will never see

and he never sees

the other

the earth itself is always between them

yet he leaves messages

concerning celestial bodies

as though he were telling of his own life

and in turn he finds

messages concerning

unseen motions of celestial bodies

movements of days of a life

and both navigators call out

passing the same places as the sunrise

and the sunset

waking and sleeping they call

but can’t be sure whether they hear

increasingly they imagine echoes

year after year they

try to meet

thinking of each other constantly

and of the rumors of resemblances between them.

Love you, Dad